PRESERVING THE

STUDEBAKER Tuck

LEGACY

Studebaker trucks, like its

cars, were just far enough off center to appeal to drivers who wanted

something out of the ordinary.

Written by GEORGE HAMLIN photos by GEORGE NAMLIN and ATHS ZOE JAMES LIBRARY

wheels of time March /April 2008 www aths.org american truck historical society

It shouldn't catch me off guard as often as it does some Jasper in the Burger King parking lot Will look at one of my trucks and opine, “I never knew Studebaker made trucks.”

Abort all one can do is sigh and give the offender the “Thursday Afternoon 5 Minute Studebaker Update.”

There's an informal subgroup within the 12,00 member Studebaker Drivers Club, of which I am a member, for people who have this affair going with the Studebaker truck. That’s probably because these machines were often just far enough off center to appeal to those who wanted sonmething out of the ordinary, much like the Studebaker.

There should[ be more of these trucks around than there are. Studebaker muffed the opportunity maybe one of the biggest to be a big player in trucks.

Since the latter part of the 19th century. Studebaker's vehicle works (dating from 1852) had been the world's largest. A renowned manufacturer of horse drawn wagons, Studebaker was quick enough on its corporate feet to envision the transition to motorized transport but was curiously slow to anticipate the truck market.

It was not until 1914 that a commercial Studebaker appeared, but between 1917and 1927 the company left the commercial vehicle field altogether. When it got back in,

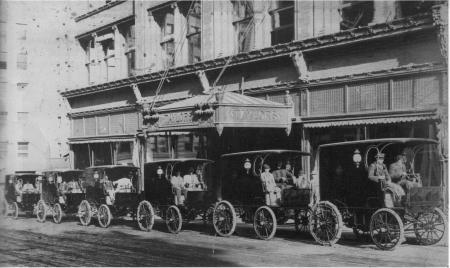

HIGH WNEELIN

A well know maker of horse

drawn wagons, Studebaker made the transition to motorized transport

in the second decade of the 1900 with these classic high wheelers: a

1913 model 5 (above) and a series of Model 2020b panel delivery

trucks, capacity 800 LBS, owned by John Taylor. Both photos are from

the ATHS Zoe James Library. slow expansion characterized the

commercial Studebaker line until the Pierce Arrow Acquisition.

In 1930 all Studebaker and

Pierce commercial production was moved to the SPA Truck Corporation,

“SPA” representing Studebaker Pierce Arrow. At that point,

Studebaker was off to the races for a while. The SPA line comprised

Pierce and Studebaker S Series trucks up to 2 tons.

In 1932 Studebaker acquired controlling interest in White Motor Company, thus bringing White and Indiana trucks into SPA, which was now marketing four brands of trucks. Studebaker was poised to be come one of the country's big ticket truck builders.

Unfortunately, the country was in the midst of the Great Depression. Compounding the poor economy was a classic blunder on the part of Studebaker managements, mostly in the person of Albert R. Erskine.

Erskine grossly misread the economic picture and spent the company nearly into oblivion by continuing to pay dividends for years on zero profits. Erskine was convinced, along with some political and business leaders, that prosperity was just around the corner.

Once all of its money was gone, Studebaker found itself in receivership and had to sell off Pierce and White to generate ready money to keep the company going. Erskine apparently felt that the honorable thing to do was to shoot himself, and he committed suicide.

Studebaker trucks and cars continued to be produced during receivership. For one thing, a truck line was a very good way to use existing engine tooling and bring unit costs down on the rest of its products. In addition, a market for these products still existed.

In 1934 Studebaker offered the T series(with Waukesha power in the 3 ton models); in 1936, cab forward jobs; in 1937, the J series; and in 1938, the K series. (We do not know why the alphabet was followed so oddly in South Bend, Indiana).

Along the way a very smart ½ ton job called the Coupe Express was introduced in 1937 to 1939. It had passenger car sheet metal up front and a pickup box on the back. This was highly uncommon, and would remain so until the mid 1950's when the El Camino and Ranchero pickups, though very early pickups from many manufacturers certainly used the idea out of necessity.

Meanwhile, in the heavy jobs, Hercules engines replaced Waukeshas. Market share during this period had been in the neighbor hood of 1%. In 1941, Studebaker finally got serious about trucks.

The new M series covered the lower portion of the truck market. There was the M5 Coupe Express, which did not look like a car anymore; the M15 standard truck, and the M16 heavy duty job. Ratings were ½, 1, and 1-1/2 ton, respectively. In its service life through 1948, the M16 could be optioned up to the 2 ton range, and a late entry after the war, M17, was so rated.

Did we say war? Studebaker trucks were right there. Even before World War II started, Studebaker had been selling trucks to the French Army. The Germans apparently thought they were pretty good trucks. Too, because after France fell the Germans used them throughout the rest of the war. The Chinese also used Studebaker trucks on the Burma Road.

But it was the M series that

would make the definitive statement about Studebaker trucks in that

conflict. Based on the M. Studebaker's US6 was made in 6X6 and 6X4

varieties and powered by Hercules engines. Studebaker built them at

the rate of 4,000 a month throughout the war.

Sturdy and Fashionable

Having acquired

controlling interest in Pierce Arrow and the White Motor Company by

1932, Studebaker was poised to become one of the country's l3eading

truck makers. “Studebakers are profit makers,” touted the

company's advertisement from 1932 (opposite page, top). Poor

management and the Great Depression changed the company's fortunes.

Still Studebaker made some excellent vehicles, including a 1934 2

axle dump (opposite page, bottom) operated by Wm. J. Alexander &

Sons in Philadelphia; a 1936 model JM20 (above) operated by Union

Transfer in Lexington, KY.; and a 1939 L5 Coupe Express (right)

operated by Ray Woods Tire Store in Dallas, Texas.

To this day you can recognize the Studebaker military truck by its slanting windshield and vent windows, left over from the Civilian truck from which it was adapted;. And when we say; “to this day;,” we do mean to imply that countless US6 trucks are still in service around the world. They are particularly cherished in Russia, where so many remain from Lend Lease production sent to the Soviet Union. (At one pint the words “Studebaker” and “truck” were almost interchangeable in Russia, much like “Kleenex” and “tissue' or 'Frigidaire' and 'refrigerator' are in other areas).

The US6 truck was not Studebaker's only wartime product. The company also produced 63,789 Wright Cyclone engines for the B 17 fleet and 15,124 Weasel light weight tracked vehicles as well as postwar military Reos made by Studebaker under defense contracts.

Studebaker was 'first by far with a postwar car' but marked time with the truck line. The 1945 model M15 even retained the military swing out windshield. Sales were satisfactory enough: over 43,000 in 1946 and nearly 68,000 in 1947. Eventually, of course, the seller's market faded and it was time for something new.

Instant Recognition

The

license plate on this K model (above) operated by Pennzoil reads

1940. Studebaker's US6 (right), built from 1942 to 1945, is instantly

recognizable, according to George Hamlin. 'Note the stylish blending

of the military front clip with spare fenders and the civilian cab

with slanted windshield and side vent windows.

Enter Robert Bourke, later to find fame with the 1953 Starliner and Starlight and the 1949 Ford. Well, fame may not be the right word; in each case his talents ended up credited to others. The Ford was an after hours favor for a friend in the case of the 1953 Studebakers, all the credit went to the styling house that Bourke worked for, Raymond Loewy Associates. Nobody much cared who designed the Forty-Niner Studebaker trucks either, but Bourke certainly made a job of it.

The new R series Studebaker trucks had a double wall pickup box, instruments accessible from the engine side, very modern styling, and fully enclosed running boards. Initial reception of these trucks in the field was gratifying, with sales in the 60 some thousand range for a while, but then began to fall: 45,000 in 1951, 40,000 in 1952, 23,000 in 1953.

It was time for a face lift to boost sales. A one piece windshield and a new grille resulted in 1954 sales of just over 12,000 units a major disappointment.

At that point Packard bought the whole Studebaker operation. Studebaker trucks, now designated the E series, began a different and more serious direction. Now available were V8 engines (four years after they should have been), two tone paint jobs, automatic transmissions, 5 speed transmissions, and 4 wheel drive (courtesy of NAPCO).

Modern Styling

The 1 ½ ton

stake

bed (above) is probably a 1955 E series, Hamlin notes. 'Observe that

the grille overlay and the new 1 piece windshield updated the

previous styling in the 2R16s (at left), built from 1949 to 1953”.

The Studebaker

product offering was greatly expanded. In 1956 the Transtar name

appeared. (international, marketing a load-star and a work-star,

lusted after that name for a decade before they finally got it.)

The Studebaker

product offering was greatly expanded. In 1956 the Transtar name

appeared. (international, marketing a load-star and a work-star,

lusted after that name for a decade before they finally got it.)

Much of the serious truck equipment that was being offered by the Studebaker line during this period was being offered at the urging of its biggest truck dealer: Whattoff of Ames, Iowa (see the article “Whattoff's Trailer Toter's, “ Wheelsof Time, November/December 1989).

Whattoff's Toter operation dramatically changed the business of modbile home transport, with its expandable wheelbase Studebaker hauler. Sales were brisk. By 1962, Whattoff offered diesels, air brakes, Bostrom seats, and 5 speed overdrives.

William Cannon and Fred Fox, writing in “Studebaker: The Complete Story”(Tam books, 1981) estimated that Studebaker built over 150 different models after World War II, and allowing for differences in wheelbases, engine, and axles, the total would exceed 1,000varieties.

And yet there were major obstacles, beginning with the dealer body. Dealers were required to take a few pickups each year as a condition of franchise, but most of them didin't know how to sell them. Many dealers simply ignored the requirement, and those who did comply with it bought only the requisite two or three and sold them off at cost just to be rid of them.

Studebaker had some 80% of the truck market covered, if only people could be induced to buy the things. There was another obstacle too: obsolescence. Remember the new trucks of 1949? those trucks remained in production until 1964, with different wi8ndshields, equipment, paint jobs, and cleverly altered grilles. But by the late 1950s the trucks were in serious need of updating. Competitive trucks were simply bigger, and truck drivers don't like feeling cramped.

To cure the outdated design, the Champ line was introduced in 1060 for ½ and ¾ ton units. Based on the lark passenger car, the Champ offered more up to date looks and more room, though the pickup box was retained from previous years. What the heck, pickup boxes didn't have to match the cabs in those days.

Later on Studebaker bought tooling from dodge for a larger box when Dodge abandoned its Swept side design.

The music stopped in December l963, when Studebaker's South Bend plant closed. (Its entry in the postal truck field, the Zip Van, continued in production at the Met-Pro plant in Pennsylvania for another six months or so). Newman & Altman, who purchased the rights to the Avanti car and made a going proposition out of it for decades, also purchased the truck rights but never re-entered that business.

THE HAMLIN COLLECTION

As for me. the Studebaker truck bug bit me in college. I used to hang around the Whattoff dealership in Ames while the Toter operation was going full blast. I should have been studying something but I would sit in one of the big jobs and think, “Some day...”.

Some day eventually came, one truck at a time, until I had six of them: from ½ ton to 2 ton GVW. The trucks pictured along with this thumb nail history represent different eras in Studebaker's postwar truck production.

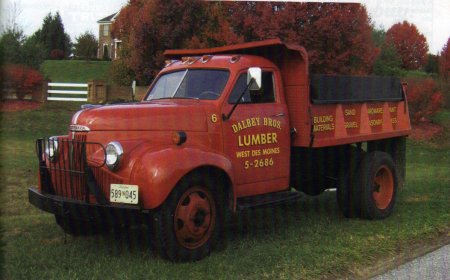

The 2 ton 1948 M16 dump truck (below) has spent its whole life in Maryland, despite the sign age on the side. It has a Hydrovac brake booster and a 2 speed vacuum actuated rear axle.

The sign age commemorated a place I used to work. Unfortunately, the yard's owner was stuck on GMC and Chevrolet trucks, so I did this up as “the truck he should have had” and sent him a photo. (By which time the yard was 20 years gone).

A STUDEBAKER FAN

George Hamliln has six restored Studebaker trucks, including a 1951 ½ ton delivery van (opposite page, top) and a 1964 Zip-Van (opposite page, bottom), as well as a 1948 M16 (below) with Gar Wood dump body.

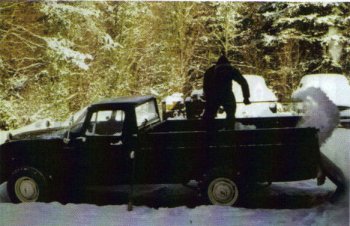

A weld built wrecker body added to this 1960 Studebaker Transtar (above) makes a nice looking unit.

The dump body is by Gar Wood yes, the same Gar Wood who raced speed boats also made truck bodies later on.

My 1951 ½

ton 2R6 delivery van (see page 22, body by Boyertown, was rescued

from the waters of Bull Run. This truck originally delivered, Tom's

Roasted Peanuts, at 5 cents a bag, and was sold by Boyertown's dealer

in Rockville, Maryland.

My 1951 ½

ton 2R6 delivery van (see page 22, body by Boyertown, was rescued

from the waters of Bull Run. This truck originally delivered, Tom's

Roasted Peanuts, at 5 cents a bag, and was sold by Boyertown's dealer

in Rockville, Maryland.

Again, the sign age is more about me than about the truck. Inside it's as sparse as sparse can be, all business and all gray.

At the time I bought it in 1978, this was one rough truck. The boyertown company still had all the panels except the roof cap, and offered to take the truck back and re-manufacture it all new and shiny. I probably should have taken them up on it. Wonder what the car show committees would have said about a 1951 truck, newly re-manufactured by its original body maker?

This model has the original Forty Niner style grille as introduced two years earlier, plus an interesting dealer optional grille guard out in front of it with a neat “S” in the middle.

The 1 ton 1960 Transtar wrecker (above) has 4 wheel drive and went originally to a dealer in Vermont, whose towing capability consisted of a boom bolted to the pickup bed. I changed that jury rig for a real Weld Built wrecker body and laid on sign age for the Studebaker dealer in Des Moines where I used to hang out in the 1950's. Unfortunately, that dealer was out of business by 1960 and his building had become a Trail-ways bus depot, but why let things like that get in the way of a nice finishing touch?

This is the same cab as the 1951, but Studebaker's stylists put a cleverly designed “we mean business” grille over the original fenders, extending the front projection by a few inches. The front is partially obscured by the Meyer snowplow mount, and that's not just for looks, we've cleared many a drive with it.

This truck also has one of the strangest tire sizes I've ever come across: 8X17.5. You don't find those tires at Sears.

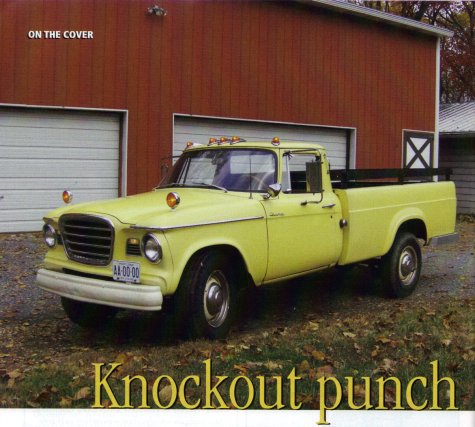

My ¾ ton 1962 7E12 champ pickup (see pages 16 and 26) was originally sold to the U.S. Government. It was used as an agricultural extension agent's truck in Iowa ( the Department of Agriculture operated an office in each of Iowa's 99 counties) and was sold at GSA auction in 1972.

It spent many years painted black, went to yellow around 1980, and now has all the factory gadgets I could hang on it, from clearance lights to the rear step bumper. It also has a Hill Holder, 5 speed overdrive transmission, and a sliding rear window, none of which you could get on any other pickup in those days. When it was delivered to the Feds, all it had extra was Class A turn signals and a heater.

I almost didn't get this truck. The GSA had a dozen of them in that sale, and one fellow bid high on all of them and forgot to sign his bids. Occasionally on the odd autumn afternoon, when the wind sweeps right behind the rain, I feel sorry for the chap, but the feeling passes.

The 1962 7E28 Transtar 1 ½ ton bus (not pictured), with body by Thomas, is an other government job. Instead of children, this bus was used to transfer select adult passengers (with metal bracelets) in the area of the District of Columbia from one accommodation to another. The bus has no seats today, and is used as live in headquarters at swap meets.

Studebaker was offering an astonishing array of wheel bases for its trucks in those years. This one is no a 171 inch wheel base, and seated 28 when it had seats, but you could have had up to 195 inches for really big buses. I've had several leaves removed from the rear springs to bring the back down, because the bus is no longer called upon to carry 6,000 pounds of prisoners.

My ½ ton 1964 8E5FC Zip Van postal delivery ( see page 22), body by Met Pro, was yet another Government truck, the survivor of an order of 4,328 run off in late 1963 and 1964. It was the only unit body Studebaker ever made, the last model made in the U. S., and the only one to offer an automatic transmission as standard equipment.

Studebaker may not have taken the share taken the share it wanted out of the truck market, but It played hard and made solid products.

With an 85 inch wheel base and right had drive, it's quite nimble and maneuverable. Its rear axle pretty much limits it to 50 miles per hour, and at that speed the engine is really buzzing. ( Car Life went overboard by pronouncing it “The Ideal Town Car” in early 1964).

I'm probably displaying shameful favoritism here, but most postal delivery trucks are mud ugly and this one is actually cute. GSA auctioned these off by the dozens around 1972 – 1973 much later than the five year called for by regulations, because the drivers were so attached to them. I spoke with one driver who said he used to stay after hours to wash and wax his Studebaker Zip Van. If that's not a testimonial, I don't know what one would be.

That completes the backyard Studebaker tour. The best way that I can summarize this company is that Studebaker may not have taken the share it wanted out of the truck market, but it played hard and made solid products. Had things taken a different turn in the 1930s, Studebaker would have been an industry leader.

Studebaker did its darnedest with limited funding, and came up with some clever ideas along the way that made a difference. Like many other truck manufacturers that went by the way side, more sales would have cured everything that ailed them.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: George Hamlin lives in Clarksville, Maryland. A retired technical writer for the U. S. Navy, Hamlin joined ATHS in 1984, and is a charter member of the Baltimore Washington Chapter.

Released after

years of honorable government service, this 1962 Studebaker 7E12

Champ is a winner once again.

Story and photos by George Hamlin

Ten years in the field and it was time to muster a bunch of these USDA Studebakers out. And I do mean “in the field”. The trucks were used lby agriculture extension agents in Iowa and put in a lot of time in the mud and the corn.

A whole bunch of them, went on the GSA auction block at once, some with ladder racks, some with tool boxes.

When I heard that these Champs were up for auction, I ask my brother in law to pick out a nice one and bid on it if he would be so kind (as I lived 1,000 miles from Des Moines, where the auction was scheduled).

By “nice.” I meant as little rust as possible. Running gear I could always fix, I figured, but rusty metal was something else.

The joke was on me, of course. It usually is. Ten years of service in Iowa winters and I expected low rust?

Actually, the Champ that I bought, a 1962 Model 7E12, didn't look too bad. That perception changed once that truck landed in the body shop for the paint. I began getting regular phone calls:

“Um, you really should have new doors”.

“Um, this floor really needs replacing”.

“Um, the cab corners are shot and so is the right door post”.

All were summoned from South Bend, Indiana and yes, they had all of it and installed. As cab corners aren't a stock item, we ordered the whole cab back and cut them out. The guys at that body shop were really talented, I should mention.

I picked a nice Plymouth yellow for the truck body but left the inside of the box black. It's not stock by a mile, but I knew that I'd never put anything in the box if I painted the inside yellow.

Did I mention that we put in a new tail gate at that point too?

My Champ has got all the toys now the things the government didn't order for some strange reason: Vent shades, chrome turn signals and grille, front fender trim, clearance lights, rear sliding window, step bumper, grab handles, stainless wheel caps and trim rings, Hill Holder. West Coast Mirrors, a new process 5 Speed overdrive, radio, and folding seat backs. It's hard to stop once you start spicing up a truck, as most of you who have ever gone through a truck restoration already know.

Most satisfying of all one of the chaps at work was a Ford fancier, another swore by his chevy. One day all three of us went out to get some fire wood. Now, pickup owners all know the one upsmanship involved in that exercise: who can haul out the most wood?

Hee, hee. It was no contest. Bring on the next challenger

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: George Hamlin is an A”THS member in Clarksville, MD.