A longtime student of automotive history. I have often been intrigued by how many times really interesting Or exciting cars are developed by struggling, marginal companies. Our latest Motor City Milestone is a good ease in point. It was literally the last creative gasp of one of America’s oldest automobile manufacturing companies. The company was Studebaker, and the car was one of the most interesting and exciting automobiles to come on the scene In the 1960s: the Avanti. Here, in capsule form, is the remarkable story of a remarkable car.

Like two other Studebakers we have featured in this column, the UT Hawk and the Wagonaire, the Avanti cane to life when Studebaker was on its last legs in 1962 and ‘63. The Hawk coupe and the Wagonaire were imaginative redesigns of Studebaker cars that had been in production for some time. But not the Avanti. Here was a new car that started with a blank sheet of paper in early 1961, that saw operating prototypes in one year, and production cars a few months later. And this development-speed record was not set by a General Motors with its vast resources, but by a struggling little ear builder in South Bend, Indiana. beset by shrinking sales and empty coffers.

Studebaker had struggled through the 1950s, but then bounced back briefly in 1959 with the introduction of the compact Lark. which sold well at first. But then the arrival of compact competition from the “big three’ in the form of the Ford Falcon. Chevy Corvair. and Plymouth Valiant put Studebaker back on the ropes. About this time, Studebaker got an energetic and creative new CEO, Sherwood Egbert., who proceeded to shake up South Bend in a big way The Wagonaire and the Hawk were two noticeable results. And the Avanti was the most dramatic.

The idea came to Egbert in early 1961. He knew he wouldn’t be able to retool the now aging Lark line for at east two or three years. He was looking for a new car that would generate showroom traffic whether or not it sold in huge quantities itself. Egbert thought it should be a sporty high - performance automobile. It also had to be all new and unlike anything else in the Studebaker line, yet it also had to be something Studebaker could design and build quickly, and on a shoestring.

That was a tall order indeed. In January 1961, Egbert contacted noted industrial designer Raymond Leowy to see if he would be interested in the project. Leowy had done design work for Studebaker on several occasions In the past. Within weeks, Leowy Had assembled a design team and set to work in a house in Palm Springs. California. Three experienced designers, Bob Andrews. John Ebstein. and Torn Kellogg completed the team. Within weeks, the concept was worked out, a clay model had been approved by the Studebaker board, and engineers In South Bend set to work to turn the design into a car. The chassis came from the existing Lark convertible, the engine was Studebaker’s sturdy 289-CID V8, and the fiber-glass body was built by Molded Fiberglass Products, the builder of Corvette bodies.

The chassis received a stiffer suspension for better road holding and the engine was tweaked for more power by none other than legendary racing genius Andy Granatelli, But the real genius who made the Avanti work mechanically was Gene Hardig, head of Studebaker engineering. Incredibly, this whole process of creation was worked through, and limited production began barely a year and a half after Egbert had first called Leowy.

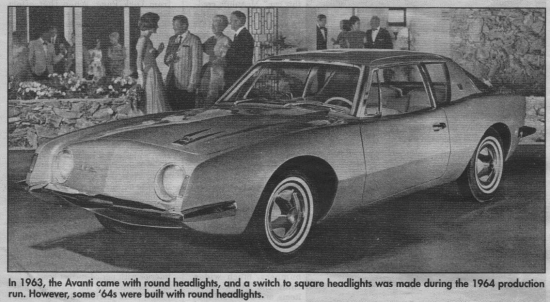

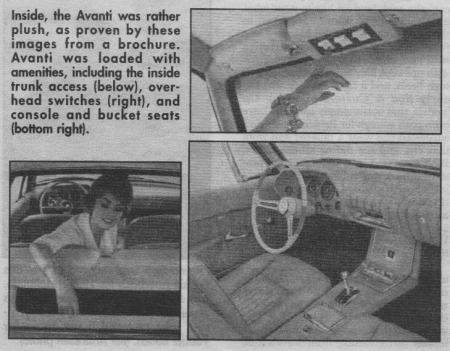

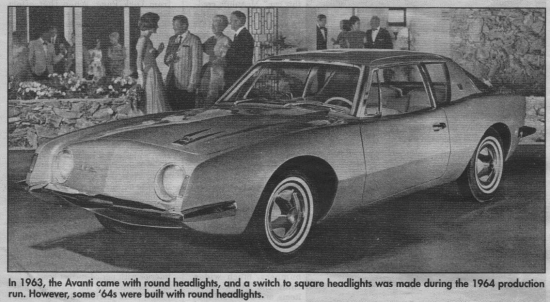

And what a striking car it was! The four-passenger coupe had a long hood with virtually no chrome ornamentation. There ‘as no grill, only an air intake under the bumper Anticipating style trends today, the Avanti’s deck was short and high. Indeed, the car rode higher on its rear suspension than the front, which gave it a distinctive “nose down” attitude. The side profile was a distinct Coke bottle shape, Inside were bucket seats, full instrumentation, including a tachometer, and controls on a console over the windshield. A full range of transmissions were available, including four on the floor, and the first use of disc brakes in an American production car ensured stopping power as good as the acceleration. There were two supercharged engines available, which later powered the Avanti to some new American land - speed records. Considering the source of the mechanicals, and the hasty development, the Avanti turned out to be a remarkably well-done grand touring car.

But it was all too late. Buyers

were turning their backs on any Studebaker, because it looked like

the company would soon quit. Slow production of Avantis in the early

months caused early buyers to cancel their orders. By the end of

1963, Studebaker shut down its South Bend production line including

Avanti production. A meager 3,834 1963 Avantis and 809 1964 models

were built. Two years later, the last production of Studebaker cars

anywhere including Canada) ceased. But there was a surprising

postscript to the Avanti story. Two South Bend Studebaker dealers,

Nate Altman and Leo Newman. bought the design rights and the tooling,

and proceeded to build Avantis for years thereafter using Corvette

power trains.